(Originally published at The Jewish Journal http://www.jewishjournal.com/culture/article/q_a_with_author_claude_knobler)

Author Claude Knobler talks to Lori Gottlieb about bringing an African 5-year-old into a neurotic Jewish family more than a decade ago, an experience he recounts in his recently released “.”

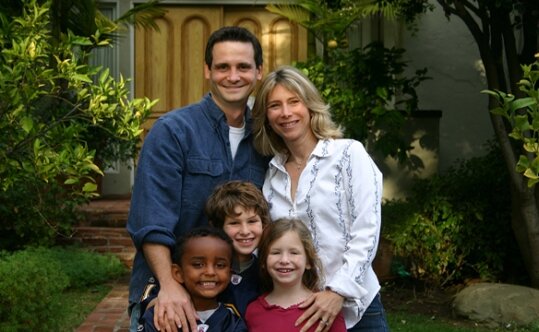

The author Claude Knobler with his wife, Mary, and their children, Nati (lower left), Clay and Grace. Photo courtesy of Claude Knobler

Lori Gottlieb: You and your wife were raising two biological kids — 7-year-old Clay and 5-year-old Grace — and had no intention of expanding your family. Then you adopted a 5-year-old boy named Nati from Ethiopia after one of his parents died of AIDS and the other became too sick from AIDS to care for him. What led to that decision?

Claude Knobler: I had never thought about adopting, but one day I read an article in the Sunday paper about an orphanage in Ethiopia. I took the article to my wife and said, “You know, we should consider doing something.” The embarrassing truth is that I thought she’d say “no” and that I’d get credit for wanting to do this very humanitarian thing without actually having to do anything. But she said “yes,” and so, we were off.

It was kind of an odd whim, but it’s also true that my mother was a survivor, that she’d been hidden in a Catholic orphanage in Belgium during World War II and then adopted by an aunt after her own parents had been killed in the Holocaust. And I grew up knowing that the world depended on the idea that people who can help other people have an obligation to do that in some way. My mother would never in a million years have suggested I adopt a child from Africa, but in a roundabout way, it was still her idea. So, like all nice Jewish boys, I’m doing exactly what my mother told me to do, even though she never actually told me to do it.

LG: A lot of parents worry about their children, but you had added worries related to bringing an African child grieving the loss of his biological parents into a Jewish-American family in Los Angeles. What were you most worried about?

CK: One of the most shocking things I learned as Nati’s father was that I was really, really bad at worrying. Which is strange, because I get a lot of practice. Continue reading

(

(

By Claude Knobler ()

By Claude Knobler ()

It was a lot easier before my son learned to speak English.

It was a lot easier before my son learned to speak English.