Lesson Three:

THERE ARE NO APPLES ON OAK TREES:

HOW TRYING TO TURN MY ETHIOPIAN SON INTO A NEUROTIC JEW TAUGHT ME IT’S NATURE, NOT NURTURE

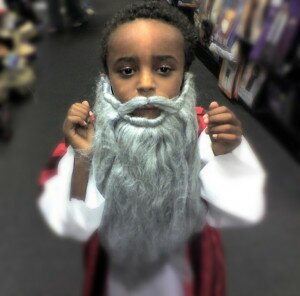

My son had a beard the day we met.

My son had a beard the day we met.

Or so I thought at the time. Really. My very first thought the first time I ever laid eyes on Nati was, “Huh, I didn’t know he had a beard.”

He didn’t. Of course, he didn’t. Five-year-olds don’t grow facial hair. I should have taken that first look at him and thought to myself, “I wonder why my son has a string attached to his chin.”

But I was tired from flying halfway around the world, sick to my stomach, and more scared than I’d ever been because I was about to meet a five-year-old Ethiopian boy, spend a week with him, and then fly home and spend the rest of my life, every single day of it, being his father.

So I thought he had a beard.

Stitches. What he had, of course, were stitches.

Nati had run into a table and someone at the orphanage had done such a poor job of giving him stitches that they’d left the string used to sew up his cut dangling from his face.

If I’d known why Nati needed stitches that day, I’d have been able to answer one of the most basic questions every parent wonders about. But I thought he had a beard, which is too bad, because if I’d been just a little bit more focused I might have saved Nati and myself six or seven years of trouble.

Here’s what it was like the week I met my son.

I flew about halfway around the world and checked into a surprisingly nice hotel in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. The hotel had a wonderful lobby and a very pleasant uniformed doorman. Outside, across the street from the hotel’s beautiful front lawn, was a muddy not-quite road, lined with tin huts. There didn’t seem to be any real sort of sewage system across the street from my hotel, so while the older people sat by the huts, all day, every day, the children played alongside unimaginable filth. I ate dinner at a nice restaurant in the hotel, slept well, and then woke up with just enough of a churning stomach so that I was, for almost the entire time I was in Ethiopia, unable to be more than ten feet from a bathroom.

When I got to the orphanage that had been Nati’s home for the last six months, I got out of my cab and saw a boy standing alone, waiting for me. I recognized him from the pictures we’d been sent for the last few months, saw that he’d grown a beard since his last photo, and then, Nati walked up to me, and, as I knelt to him, he wrapped his arms around me and put his head on my shoulders and allowed his full body to sag into mine. We’d known each other for less than sixty seconds and he had already decided he was home.

In that moment I became his father and he became my son. A great deal of laughing, yelling, frustration, happiness, misery, and joy has come and gone in the years since that day, but I know without question that it was in that moment that I first became the father of my third child.

In that moment I became his father and he became my son. A great deal of laughing, yelling, frustration, happiness, misery, and joy has come and gone in the years since that day, but I know without question that it was in that moment that I first became the father of my third child.

And then I thought to myself, “Oh, that’s not a beard. It’s string. Why does he have string attached to his face?”

Eventually I got the story, first from the people at the orphanage, and then, months later, from Nati himself. The day before I’d come, Nati had been having a good time with his friends. He’d been laughing and running and getting very silly, when he ran, chin first, into a table. He’d been having so much fun he just didn’t even see that the table was there.

He had stitches. Because, again, he was too busy laughing and playing and having fun to see where he was going. In an orphanage. In Ethiopia. I’ve been to that orphanage. It was clean and the adults in charge did everything they could to love and help the kids who were living there. But there were about ten hard metal bunk beds in one tiny room where some of the kids, including Nati, slept. The classroom where they spent some of every day was small and cramped and could have induced claustrophobia in a corpse. The kids there had suffered horrible, traumatic losses that they’d be spending the rest of their lives trying to process and recover from. Yes, there was a small place to play, but it was still an orphanage and I didn’t see any other kids who were having so much fun that they were running into stuff.

And just as I should have seen that string dangling from Nati’s face and known that of course it wasn’t a beard, I should have known right then and there the answer to that old question: Are our kids born the way they are, or do we make them who we want them to be? Just how much can we, as parents, mold our children?

Here’s a hint. When your child is the sort of kid who can have a blast in an orphanage, you’re going to have a lot less influence, power, and control than you might have hoped for.

A great deal of what we consider to be parenting is about power and control and molding our kids into what we’ve decided is the best version of themselves. We remind them to say please and thank you, in the hopes that they will grow into polite adults. We demand that they keep playing on the team of the sport they no longer enjoy so they can learn about hard work and persistence because we know they’ll need those qualities later on in life. We demand they do chores so they’ll become responsible and one day be able to (please God) hold down a job. We spend much of their childhoods and our adult years with our hands on their shoulders steering them this way and that all because we are their parents and molding their characters and shaping their destinies is the whole point.

Unless it isn’t.

What if all that molding and steering aren’t necessary or even useful? What if our kids come into the world already formed? What’s the job of a parent then? Most every parent who has at least two kids has at some point noticed that his kids are different. One kid is quieter, the other more adventurous. Some kids are natural readers; others never met a tree they didn’t want to climb or cut down with the ax they plan on borrowing when no one’s looking. And yet if we don’t go further than just noticing that our kids seem to be born with personalities already inside them, we miss an enormous opportunity. If our kids are who they are from the day they’re born, isn’t it possible that our jobs as parents should be a lot more about appreciating them than molding them?

What if all that molding and steering aren’t necessary or even useful? What if our kids come into the world already formed? What’s the job of a parent then? Most every parent who has at least two kids has at some point noticed that his kids are different. One kid is quieter, the other more adventurous. Some kids are natural readers; others never met a tree they didn’t want to climb or cut down with the ax they plan on borrowing when no one’s looking. And yet if we don’t go further than just noticing that our kids seem to be born with personalities already inside them, we miss an enormous opportunity. If our kids are who they are from the day they’re born, isn’t it possible that our jobs as parents should be a lot more about appreciating them than molding them?

You might think that it would be difficult to get to know a child when the two of you don’t speak the same language, but really, it isn’t. My first week alone with Nati was spent in Ethiopia, waiting for the government there to finish processing our adoption paperwork. Nati very quickly got into the habit of running ahead of me in the halls of our hotel, hiding behind a corner, and then jumping out to try and scare me. (That tended not to work mostly because I always saw him running ahead of me to hide but also because he always yelled, “Yes!” at me instead of “Boo!” So really, he tended to look more like a very eager waiter than a scary goblin. “YES! May I help you?!”) He was a ball of nonstop energy and enthusiasm from the moment he got up until the moment he went to sleep, always singing to himself and laughing about pretty much everything he came into contact with. He was a young five, and certainly unfamiliar with a lot of what the world had to offer. TV fascinated him as it does most kids, but so did the first escalator he’d ever used. None of it scared him; he seemed to treat the whole world like an amazingly cool playground built just for his amusement.

One day at the hotel, Nati ran ahead of me as we walked into the lobby. By the time I caught up, Nati was speaking with the woman behind the counter. Then he began dancing. A moment later, the woman burst out into laughter. When I asked her to translate what he’d said that had made her laugh, she replied that my son had just told her, “Speaking English is easy for me! And I can dance, too!” When you have to tell someone that speaking English is easy in the language of Amharic, because you don’t actually know how to speak English yet—well, at that point, you’re really taking the concept of confidence and self-assurance into a whole new arena. If you’re thinking that Nati was just anxious and filled with false bravado . . . I did too. But it didn’t take long for me to realize that there was nothing false about Nati’s bravado. It was, and is, 100 percent real.

For example, Nati had only been living with us in California for two or three months when we decided to go to San Diego for a day. I strapped him into his car seat next to his brother and sister and then began to drive.

Now, before Nati came along, getting into the car and driving was a fairly simple process. First, Mary or I would decide where we wanted to go. Then, we’d tell Clay and Grace where we’d decided to go by saying something like, “This is going to be fun, we’re all going to the aquarium!” Then we’d buckle everyone in and drive off. Our family dynamic was fairly simple. It may have been a bit inverted, since I was a stay-at-home dad while Mary went off to the office every day, but still, we all functioned fairly smoothly together in a reasonably traditional way. At five, Grace was in a princess stage. She was happy to go on errands with me anywhere so long as she got to wear a fabulous gown. And Clay was a rule obeyer, like Mary and me. If the teacher said hold hands when you cross the street, we held hands every time we crossed the street. Clay has always tried to do things “the right way.” He doesn’t eat his popcorn before the movie starts, he wouldn’t dream of leaving a baseball game before it was over, and he assumed that when his mom or dad said we needed to go somewhere, that we needed to go there and that was that. Simple.

And then came Nati. And simple car trips stopped being quite so simple.

On this particular day, as I turned right onto a street and began heading toward San Diego, Nati started shouting, “No Dad, go straight!” (And yes, speaking English was turning out to be fairly easy for him, just as he’d predicted in that hotel lobby.) Nati continued to try to navigate for me, shouting out, “Go left!” and “No, turn here, Dad!” until finally I turned back to him and asked with genuine curiosity, “Have you ever been to San Diego, Nati?” Honestly, it wasn’t until he asked me, “I don’t know ziss. What is a sandee-aago?” that I went back to trusting my own sense of direction.

We got a lot of that sort of thing from the very beginning. The first time I threw Nati a football, a type of ball he’d never laid eyes on, he helpfully corrected my throwing motion. “No, Dad, like ziss!” he told me. And then he threw the ball one foot in front of him directly into the ground. That didn’t bother him, though. He just kept practicing his way, until he’d learned to throw fairly well.

In the end, it was a friend of ours who summed up Nati’s personality best. Mary and I had taken Nati to a classmate’s birthday party, where our friend Adam told us to go enjoy a cup of coffee while he made sure Nati didn’t get himself hurt. When we got back to the party, we found out that Nati had found the cake, removed the frosting spelling Happy Birthday Matthew in lovely script, and had applied it to his own face so that he could have a frosting mustache and beard. Amazingly (and because my son is indecently charming and adorable) the stunt had gone over fairly well, not just with classmates and the birthday boy, but with our very patient friends. “Nati,” Adam told us with a smile, “does things that other kids only dream of.” Truer words were never spoken.

At home, we struggled. Nati is nearly three years younger than our son Clay, but he quickly got into the habit of bossing his older brother around. Mary and I began to fume. Picking up the kids after school became more and more frustrating. I’d ask about everyone’s day, but I’d wind up only hearing from Nati. Nati was so exuberant, loud, and commanding that he often seemed to simply overpower everyone else through sheer force of personality.

At home, we struggled. Nati is nearly three years younger than our son Clay, but he quickly got into the habit of bossing his older brother around. Mary and I began to fume. Picking up the kids after school became more and more frustrating. I’d ask about everyone’s day, but I’d wind up only hearing from Nati. Nati was so exuberant, loud, and commanding that he often seemed to simply overpower everyone else through sheer force of personality.

And so Mary and I began parenting.

Or, to put it slightly less charitably, Mary and I began a long battle to try to turn our exuberant, silly Ethiopian son into a quiet, neurotic Jew, just like us.